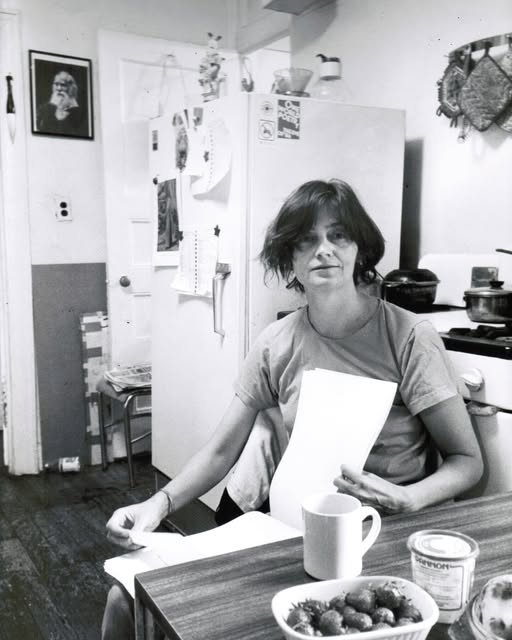

Alice Notley, a towering and unflinching voice in contemporary poetry, passed away Monday evening in Paris, where she had lived for the past several decades. She was 79. Her passing marks the end of an era and a profound loss to the literary world, where her fearless voice reshaped the boundaries of form, identity, and myth.

Notley leaves behind an extraordinary body of work, spanning more than four decades, as well as a fiercely loyal readership that grew with her through each evolution of her craft.

From her early days among the second-generation New York School poets to her later years of epics and cosmological lyricism, Notley was never easy to categorize—and she preferred it that way.

“Mostly, I just keep writing in whatever way I want to next,” she told CutBank in 2014. “I am, at this point, an epic poet – I am like Virgil – and everybody better watch out because I am the one reshaping the myth and defining the world.”

Born in 1945, Notley was raised in California and came of age in the midst of a poetic revolution. After graduating from Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, she moved to New York and married fellow poet Ted Berrigan.

The two raised a family in a community steeped in experimentation, camaraderie, and resistance to the poetic mainstream. After Berrigan’s death, she later married British poet Douglas Oliver.

The richness of her personal life—its joys, losses, and transformations—intersected continually with her poetic vision, though she resisted being reduced to any single relationship or label.

Her poetry was radical in its refusal to obey conventional limits, spanning politics, feminism, motherhood, illness, mythology, and metaphysics. Works such as The Descent of Alette and Grave of Light are not merely books—they are immersive, experimental sagas that challenge and redefine language itself.

In them, she reimagines poetic voice, often blurring the line between the personal and the universal, the seen and unseen. She wielded punctuation and space like spellcraft, invoking entire cosmologies through fragmented yet coherent incantations.

Notley was deeply feminist but resisted any simple reduction to ideological terms. “I am feminist, or I am the person defined by having loved Ted Berrigan or Douglas Oliver; I am personal, I am not personal, I am a poet of grief…” she remarked. Her complexity was her strength.

In every line, there was an insistence on autonomy—on the right to define herself, to reimagine the world on her own terms. Hers was a poetry of defiance, of vision, of deep interiority and far-reaching scale.

In recent years, even as illness shadowed her, she continued to write and publish prolifically, maintaining an unshakable belief in the poetic voice as a force capable of cosmic revelation and intimate transformation alike. Her work was translated widely and celebrated globally, and yet she remained ever the outsider, the subversive oracle reshaping myth from her Paris apartment.

Heartfelt condolences go out to her sons, Eddie and Anselm, both poets in their own right, as well as to her extended family of readers, editors, collaborators, and kindred spirits who found, in her words, both guidance and liberation.

To say goodbye to Alice Notley is to mourn not only the loss of a singular voice but to honor the electric, uncompromising spirit she brought to the art form she so fiercely defended and endlessly reimagined. She was international, interplanetary—always in orbit around new poetic possibilities. May her words continue to illuminate, to challenge, to free.

Fare thee well, Alice. The world you reshaped remains forever changed.